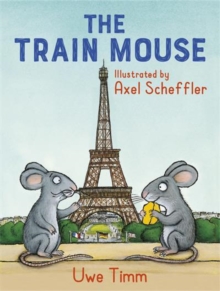

To mark the publication of The Train Mouse, here’s a slightly edited version of an article I wrote for the ITI Bulletin, which first appeared in their January-February edition (please consider buying it from an independent bookshop in these challenging times!):

When I started work on translating The Train Mouse by Uwe Timm, and illustrated by Axel Scheffler, for Andersen Press last spring, it became clear that one of the major issues was going to be Wilhelm, a country mouse from Basel who speaks in a strong Swiss dialect. Particularly since this was a children’s book, we needed to avoid sounding snobby or prejudiced against any particular race or class, while – as a parent and thus a “reader-aloud” – I also wanted to avoid sustained comedy voices and being forced to work out how to pronounce things!

From Switzerland to Swaffham

I considered, and discussed with colleagues, attempting to replicate a Swiss accent in English, telling readers that he speaks with a strong accent (or in dialect) and leaving it to their imagination, dropping in occasional non-standard bits of English, putting everything he says in italics or a different font.

In the end, after consulting the publisher, we settled on a Norfolk dialect for Wilhelm as a nod towards the place where I’ve lived all my adult life and to give him a very distinct sound that would be less well-known to most English-speaking readers than a standard Mummerset-type clichéd accent. So far, so good, but could I pull it off? I then turned to the internet to find Norfolk glossaries, phrasebooks and even a site (funtranslations.org/norfolk) that would supposedly convert standard English into Broad Norfolk.

The next challenge was understanding the Swiss, which required the assistance of a Twitter friend, who translated it into standard German for me. Here is an example which shows how different the three can be:

Swiss: »Do kömme mer nie uuse. Die Glaswänd sin so glatt und viil z hoch. Mir bliibe s ganz Läbe lang do dinne hogge«, sagte Wilhelm traurig.

Standard German: „Da kommen wir nie raus. Die Glaswände sind so glatt und viel zu hoch. Wir werden das ganze Leben lang hier drinnen sitzen bleiben.“

Standard English: “We’ll never get out of here. The glass walls are so smooth and far to high. We’ll spend our whole lives sitting in here.”

Versions, revisions and new versions

The consistent grammatical forms of Norfolk include the loss of the “s” ending in the third person, the use of “that” instead of “it”, and what Wikipedia calls “a wider range of uses and meanings” for the word “do”.

So I translated Wilhelm’s first long speech in the book as:

“thass just a fairy-tale. Per’aps that used to be like that but it’s all machines do that now. There’s no rume f’r us meezen now. Y’know … Swisserland’s no country for meezen. That’s all too neat and tidy.”

It met with broad approval, so I was emboldened to carry on with this approach. Wilhelm illustrates the extreme orderliness of Switzerland by pointing out a woman dropping a chip and immediately picking it up to put in the bin. »Gsesch« he says, which I tried out as: “Do you look,”. Similarly, »Wenn mes gnau nimmt«, sagte Wilhelm, »git’s Brotschnyde für uns Müs nüt här,« might come out as “Do you look at it like that,” said Wilhelm, “cuttin’ bread ent much good for us meezen.”

However, the publisher felt that these forms would be too confusing for younger readers, as would spellings like “hare” for “here”. A peculiarity of this project is that the translation is aimed at a younger age group than the original German – Andersen Press feels, with justification, that the Axel Scheffler illustrations will mean that the book will be bought for younger children (demonstrating yet again, the role played by publishers, parents, teachers and other book buyers as gatekeepers between children and translated books). Consequently, we ended up aiming for more of an accent than a true dialect. The obscure but lovely “meezen” was dropped in favour of “moice” ; the use of “do” for “if” (do you look at it like that), “let’s” (do we go!) or an imperative (Do you watch!) was dropped altogether; but, by contrast, the use of “that” for “it” was increased as it’s a readily-comprehensible but distinctive usage: “Per’aps that used to be like that…”

So my final version for that first example is:

“Oh,” said Wilhelm, “thass just a fairy-tale. Per’aps that used to be like that but it’s all machines that do that now. There’s no room for us moice. Y’know,” he went on, ‘Switzerland’s no country for moice. It’s all too neat and tidy.”

More rodents, more dialects, more dilemmas

Wilhelm wasn’t the end of the story, however. In the course of their travels, Nibbles (originally Mausebiber – mouse-beaver – a name which caused a good deal of anguish in itself) and Wilhelm travel to Paris, where they meet a French mouse. He basically speaks standard German, with a few words of French dropped in, which made him fairly straightforward to translate. They then end up coming to Britain with a circus. Here, the ringmaster addresses the audience in a mixture of English and German:

»Ladies and Gentlemen, ich habe the Pleasure, Ihnen a very famous Number anzusagen. Eine Number, die die Naturgesetze außer Kraft setzt. Die den berühmten Mister Newton widerlegt. Undenkbar, aber doch wahr, was Sie jetzt gleich sehen werden. Zwanzig Mäuse ziehen eine Katze.«

My first attempt:

“Meine Damen und Herren, Ladies and Gentlemen, ich habe the pleasure to present to you a very famous Nummer. A Nummer that defies the laws of nature, that denies the work of the famous Herr Newton. Incredible but true, what you are about to see. A Katze pulled around the ring by twenty Mäuse.”

Again, the editor preferred again to emphasise the accent, so the final version is this:

“And then Mr Salambo entered the ring and declared in English with a strong accent, ‘Meine Damen und Herren, Ladies and Gentlemen, I have ze pleasure to present to you a very famous act. An act that defies ze laws of nature, zat denies ze vork of ze famous Zir Isaac Newton. Incredible but true, what you are about to see. A cat pulled around ze ring by twenty mice.’”

And finally, the mice have the opportunity to get back to Germany. While they are waiting in the port for a ship, they hear some sailors speaking Plattdeutsch (Low German) and follow them to a ship bound for Hamburg, where they meet a rat, who also speaks in Platt. (Here we also have the problem of swearing in children’s books – “Schiet” being “Scheiße”, being “shit” and therefore unacceptable, and an unworkable pun – “Landratten” – “land rats” – “landlubbers” – as well as the dialect.) What to do this time?

One option for the rat was Mockney, but it didn’t sit right with Hamburg to me. Would Geordie, Scouse or Scottish be possible? Or would they locate the speakers too strongly in the wrong location? With the help of Kim Sanderson I tried a Geordie version.

The original: Der eine sagte: »Watn Schiet hier.« Und der andere sagte: »Jo. Watn Glück, in twee Doog kümmt wi no Hamburg.« … »Wat mokt ji denn hier«, raunzte die Ratte. […] »Verschwindet ünd en beten snell, dat Schip is för üns«, sagte die Ratte, »dat is nix för Landratten.« … »De Ös, verdammichnochmol, son Schiet.«

My attempt at a London accent: One evening, we heard two men who walked right past our hiding place. One said: “Cor, it’s a dump ‘ere ain’t it?” And the other said: “Yeah. Fank ‘eavens we’ll be back in ‘amburg the day after termorra.” […] “Wot’re you lot doin’ ‘ere?” grumbled the rat.

“We want to get to Hamburg and then on to Munich,” I said. “Gerraht of it, ‘n’ quick abaht it, this ship is aahs,” said the rat. “This ain’t no place for landlubbers.” / “Landlubbers,” said Wilhelm, “thass a lud a ole squit, we’re meezen!” […] For a while, we heard the ship rat digging around in the wheat, cursing: “filfy l’il beggars, cor blimey, blummin’ ‘eck…”

And the Geordie: One said: “Why, it’s propa clarty/a reet shambles/a midden heor!” And the other said: “Aye, it is an’ aall. Wuh’ll be back in Hamburg the day after themorra, but.” … “Wot yous deein heor, like?” grumbled the rat. “We want to get to Hamburg and then on to Munich,” I said. “Haddaway man, sharpish, it’s wor ship this!” said the rat. “It’s not for yous landlubbers.” […] “Dorty beggars! Blimmin eck, well ah nivvor…”

We decided that Newcastle did work as an appropriately Northern port city, but again toned it down in favour of a hint of an accent.

Revised Geordie version: One said, ‘Why, it’s proper dirty here.’ And the other said, ‘Aye, it is an’ all. Wu’ll be back in Hamburg the day after themorra, though.’ … ‘What are youse doing here?’ grumbled the rat. ‘We want to get to Hamburg and then on to Munich,’ I said. ‘Beat it, sharpish, this is our ship,’ said the rat. ‘It’s not for youse landlubbers.’ / ‘Landlubbers!’ said Wilhelm. ‘Thass a load o’ old nonsense, we’re moice!’ … For a while, we heard the ship rat digging around in the wheat, cursing and muttering: ‘Dirty beggars, blimey, blimmin’ ’eck…’

Final version: the role of the reader

In the final text, we ended up with a version where the dialects weren’t entirely consistent, which as the translator I would have ideally liked them to be. But then again few of us speak exactly the same way in every situation. It comes down a lot to how much work the reader should be expected to do – a lot in the German case, rather less in the English. What I do hope we’ve done is manage to fulfil the aims of making the voices distinctive but non-patronising and to hint at accents rather than to force parents or teachers to do too many comedy voices! In the end, it’s up to the reader to decide.

.jpg)